Coffee Codex - AWS outage

Introduction

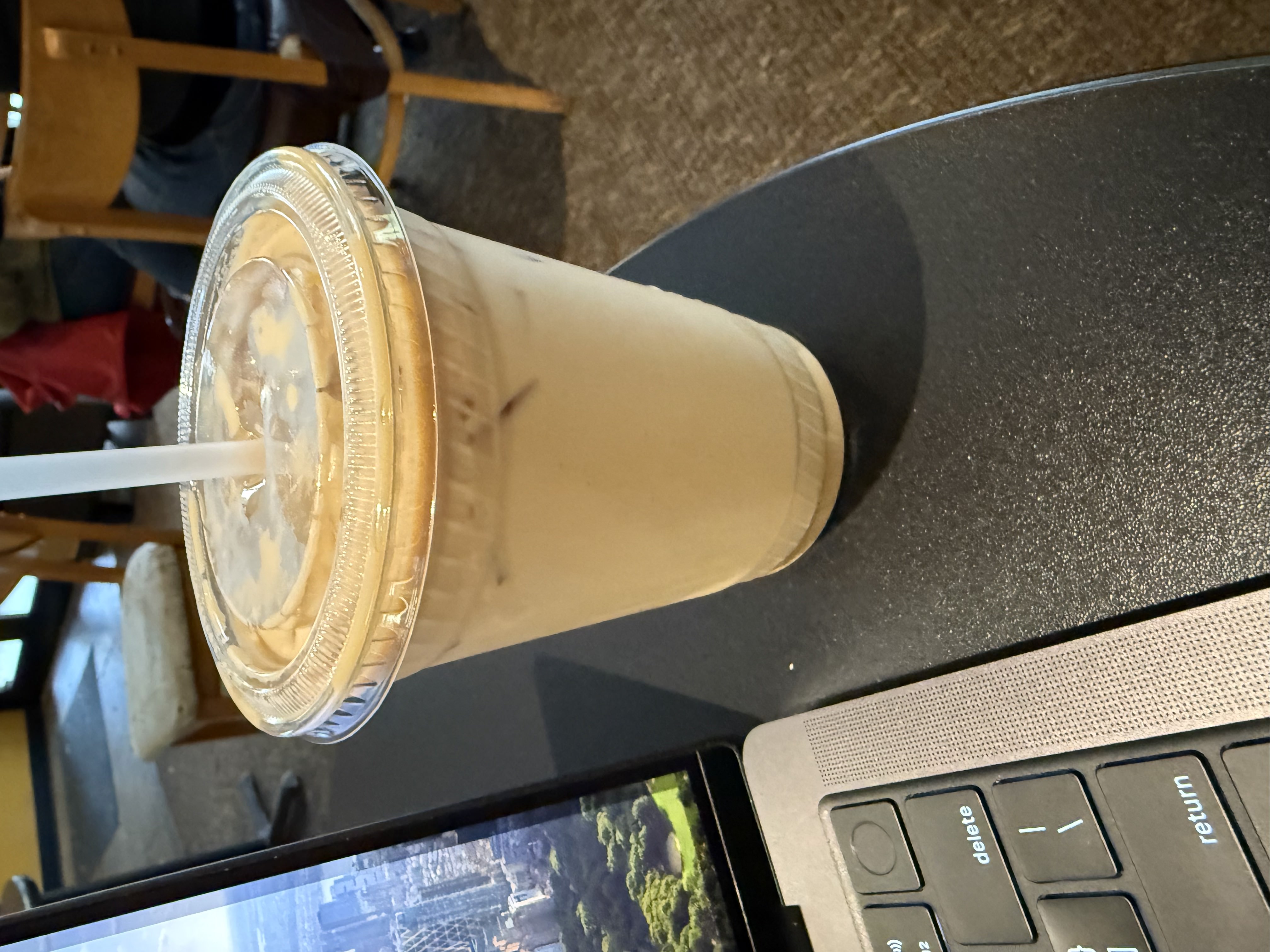

I’m at T’Latte in Bellevue, WA and today I’m reading about the AWS outage that happened in us-east-1 (and some other regions) on October 19th and 20th, 2025. I work at AWS and was lucky enough to be on-call during this time. I’m not on the DynamoDB or EC2 teams, but my service was also down during this time in us-east-1. To my knowledge, there were two incidents: the first one happened on Sunday night (PST) and the second happened Monday morning, but I’m not sure if the first one was related. I probably won’t read all of the post, but rather just understand one part.

DynamoDB Outage

How DDB updates DNS records

The reason why services could not reach DynamoDB during this time was because the dynamodb.us-east-1.amazonaws.com endpoint was unavailable. At a high level, DNS will take in a human-readable name and return its IP address. You can find the IP address of a site by using a tool like dig or https://8.8.8.8. So the applications that connect to dynamodb.us-east-1.amazonaws.com went down because they could not access their database since the record that maps dynamodb.us-east-1.amazonaws.com to its IP address had been deleted somehow.

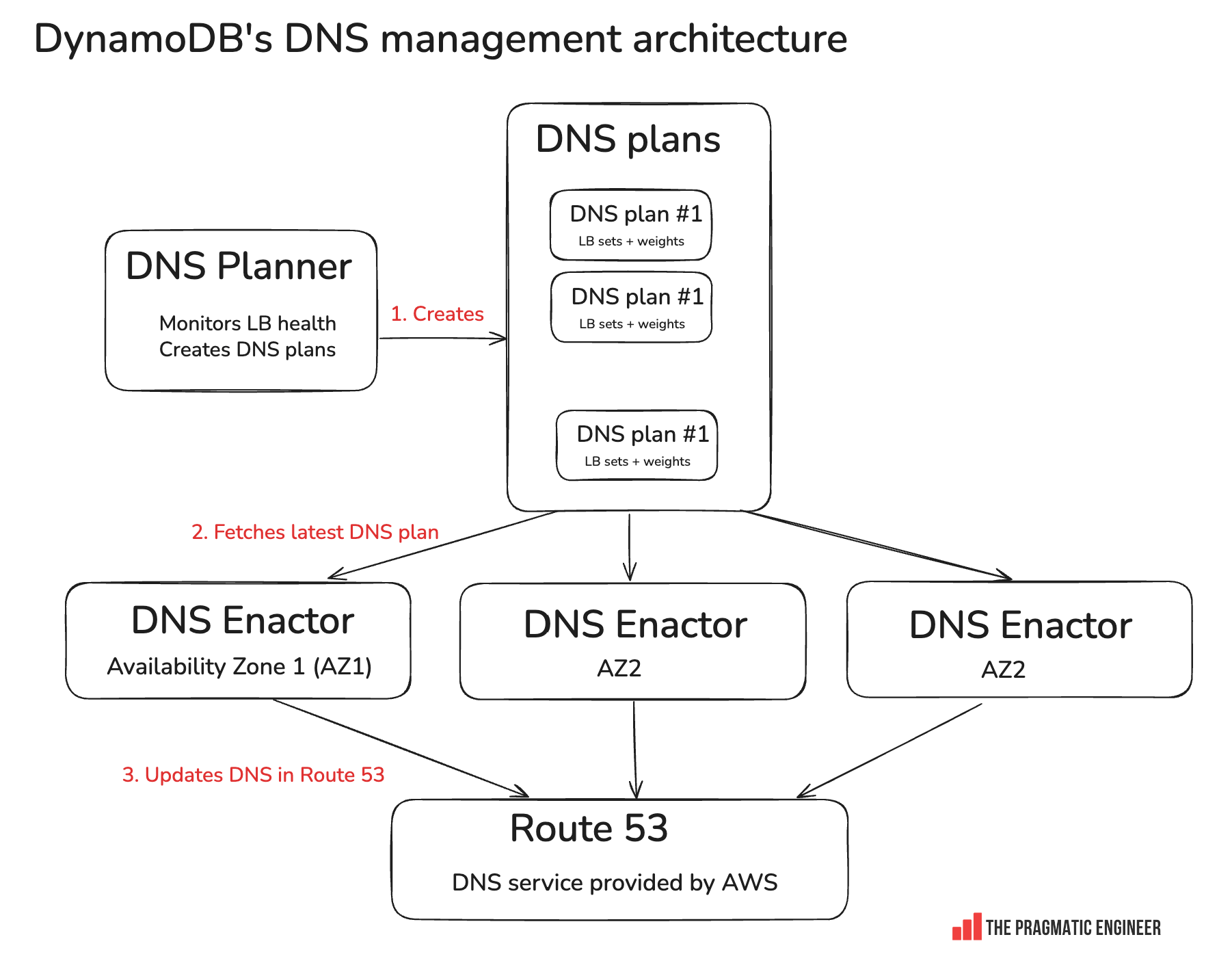

The Pragmatic Engineer blog has a great diagram that shows the architecture of DynamoDB DNS:

(credit to pragmaticengineer.com)

(credit to pragmaticengineer.com)

Let’s start from the bottom. Route 53 is where the DNS records for many services, including DDB, live. When someone runs something like

aws dynamodb query ... --region us-east-1the first step is to resolve the dynamodb.us-east-1.amazonaws.com as I mentioned before. The flow for that is Local DNS resolver → root DNS → AWS’s Route 53 authoritative DNS servers. The IP address that is used is the load balancer which the client will open a TCP connection to.

The IP addresses for DDB get rotated often so the load balancers are up to date. Since DDB has thousands of LBs that are constantly leaving and joining the fleet, the DNS records must also be updated. The DNS Planner is the service that keeps track of the current state of these load balancers. The plans it creates are something like “These 10 load balancers are good - give them these weights for routing.” It also stores the IPs for that specific load balancer.

dynamodb.us-east-1.amazonaws.com → {10.1.1.1, 10.1.1.2, 10.1.1.3, …}So DDB has these IP addresses, but it needs to actually tell Route 53 to update with the new ones, which is what the DNS Enactors do. Notice how there are 3 enactors, one per availability zone.

So what went wrong?

It was a race condition. Typically, the enactors will query the plans, check if the new plan is newer than the current one, and update it if so. The problem is that Enactor 1 experienced significant delays, so it was trying to update a plan (say Plan #100) for a while. When Enactor 1 finally finished applying Plan #100, it had no idea that newer plans already existed. Its initial “is this newer?” check had passed earlier, so it happily overwrote Route 53 with the contents of its now-stale plan. For a few moments, Route 53’s DNS records for dynamodb.us-east-1.amazonaws.com were rolled back to an older generation. At almost the exact same time, Enactor 2, which had already applied the latest Plan #103, began its routine cleanup job.

Typically, the cleanup will never touch active plans, but Enactor 2 thought Plan #100 was inactive, so it happily deleted it from the local plan registry, which wiped out the active IP address mapping in the plans.

High-level overview of the other outages

After DynamoDB’s DNS was restored, other AWS services didn’t bounce back immediately because they had built up large internal backlogs and dependencies that had broken during the outage, essentially a thundering herd. For example, EC2 couldn’t launch new instances while DynamoDB was unreachable (its droplet manager relies on DynamoDB for instance state), so thousands of servers were stuck waiting for leases to re-establish.

When DynamoDB came back, that sudden flood of retries overwhelmed EC2’s management layer, delaying recovery. Similarly, Lambda, STS, ECS/EKS, and Connect all use DynamoDB tables for coordination or configuration; their workers had queues full of failed operations that needed to replay and synchronize.