Coffee Codex - More Transactions

Introduction

For the last 2 posts, I read the transactions paper by Jim Gray. Today, I’m continuing to learn about transactions by reading this blog post by Ben Dicken from Planetscale.

The gist of a transaction is it’s a set made against the database that happens as one unit, so something like

begin;

select user from users where ...

update user set name where ...

commit;If two users update the user’s name to something different at the same time, transactions ensure we aren’t left in a state of uncertainty, since all users will see the same data.

Repeatable reads

In order to accomplish the goal, both transactions would require a consistent view of the data in the database when the transaction is occurring. This is possible in Repeatable Read mode in MySQL and Postgres, but their approaches differ.

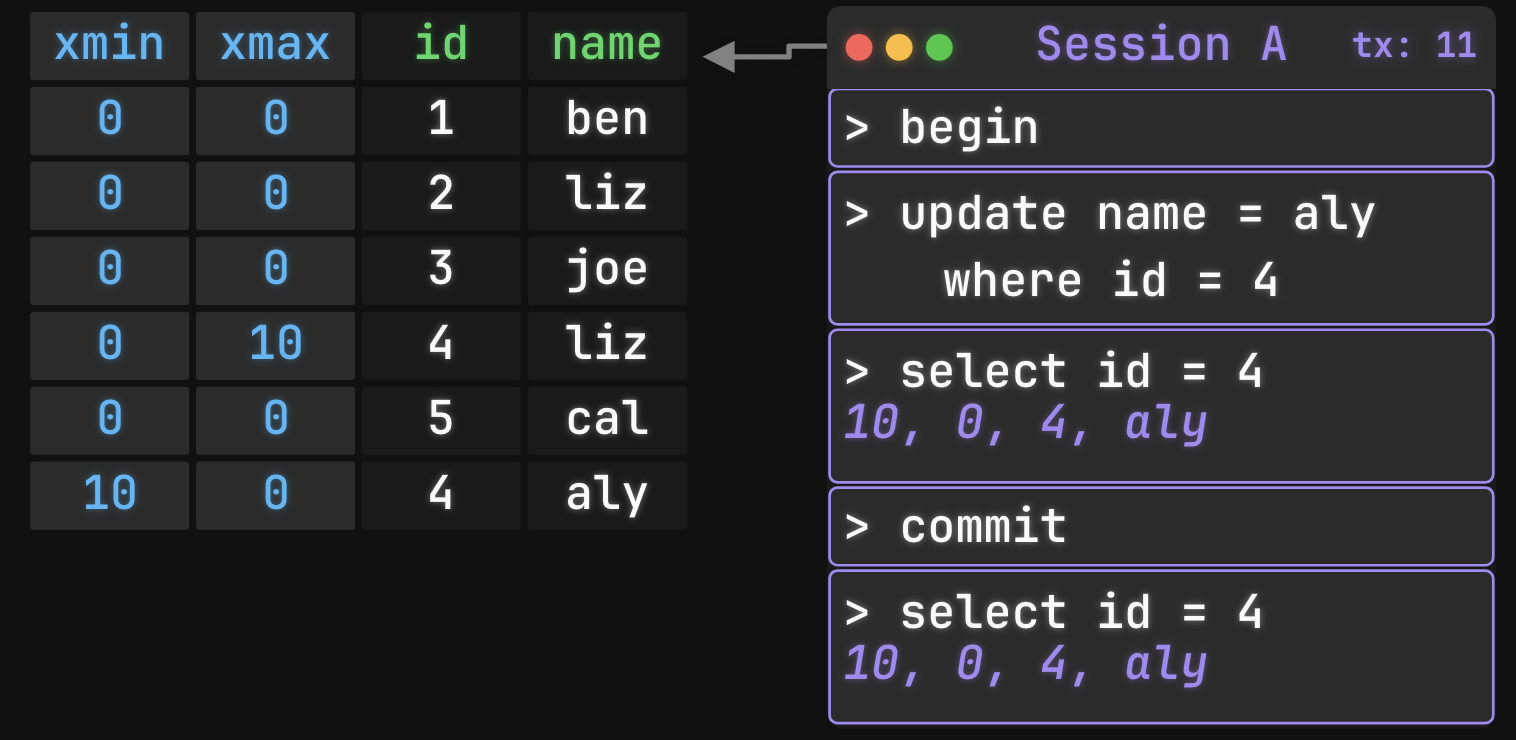

Postgres

Postgres accomplishes repeatable reads via “Multi-row versioning”. The basic idea of this is every modification to the database will create a copy of the row it modified, but that copy is not visible to other transactions until the commit command.

To keep track of the transaction ID that created a row version, Postgres also stores an xmin value, which is the transaction ID minimum. When a record is replaced or deleted (e.g. when that ID is updated), the transaction ID gets stored in xmax, which is the maximum transaction ID.

A transaction can see a row version if:

- The row’s xmin is less than or equal to the transaction’s ID (the creating transaction committed)

- The row’s xmax is either NULL or greater than the transaction’s ID (not deleted/replaced yet, or replaced by a later transaction)

I think of it like “xmax_i is the maximum transaction number where the current row is visible. If the current row is not visible, we find the row where xmin = xmax_i”.

Taken from Ben’s post

Taken from Ben’s post

When it’s time to clean up the stale duplicate rows, Postgres has a command called VACUUM FULL.

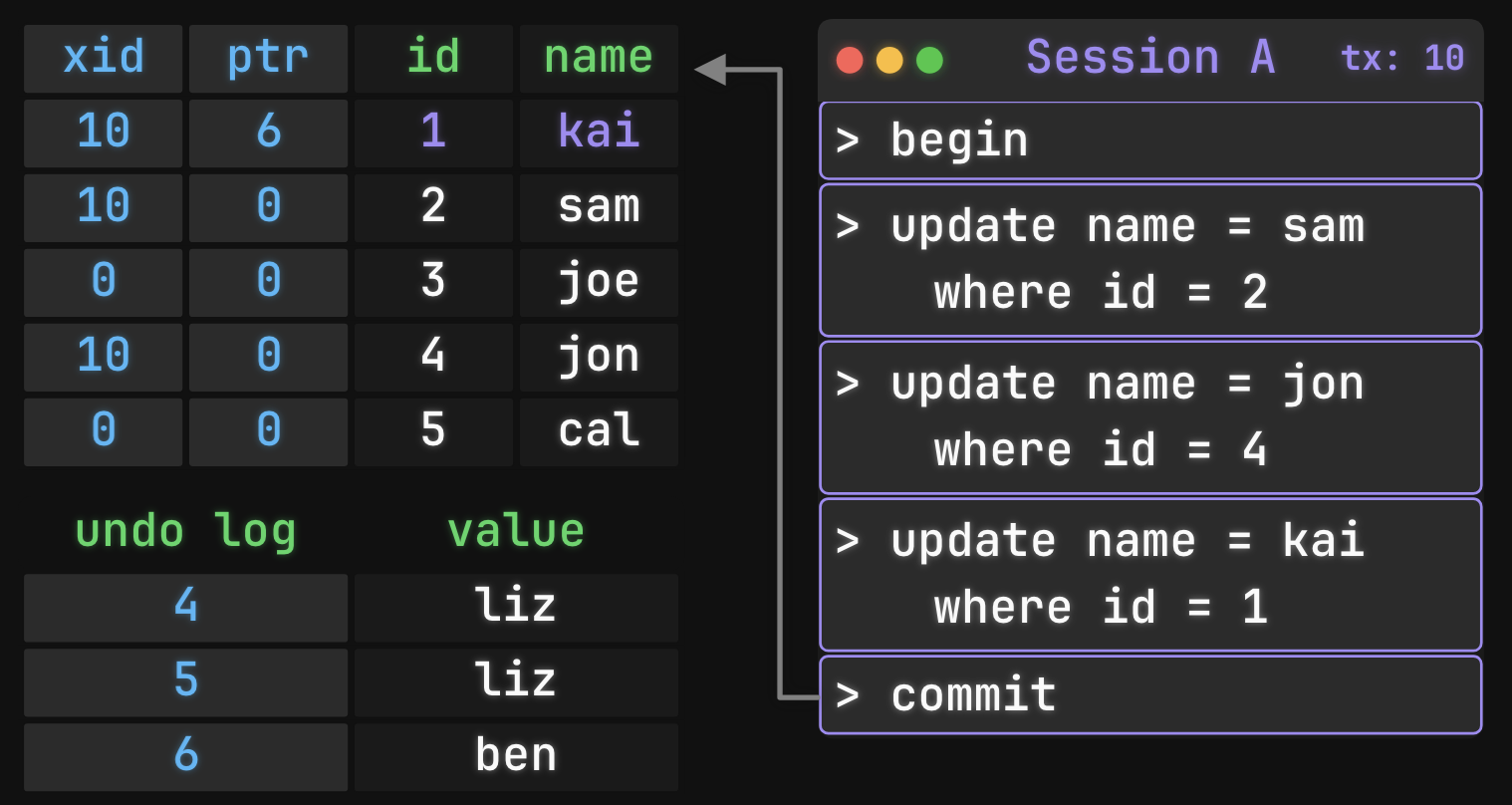

MySQL

MySQL’s approach is a bit different and aligns more with Jim Gray’s paper. Instead of keeping copies of each row like Postgres, MySQL overwrites the old row data immediately when you update it. That means less maintenance—no vacuuming—but MySQL still needs to show different versions to different transactions.

For that, it uses an undo log: a log of recently-made row modifications. Each row has two metadata columns: xid (the transaction that last updated it) and ptr (a pointer into the undo log). When transaction A overwrites a row that transaction B still needs to see, B can reconstruct the old version by following the undo log. There can even be several undo log entries for the same row at once; MySQL picks the right one based on transaction IDs.

Taken from Ben’s post

Taken from Ben’s post

SQLite

SQLite locks the entire database during a write by default lol. There is a WAL mode though where writes go to a separate file.