Coffee Codex - Replication

Meshan Khosla,Introduction

I’m at Dote Cafe in Bellevue, WA and I’m learning more about replication in distributed systems through the DDIA lecture series.

What I know

I’m familiar with the basic idea of replication in distributed systems. At a basic level, you should aim to have copies of your data in the event that your data gets lost. This can be done on an individual disk with the RAID series, and it can be done at a higher level such as having multiple database copies. Oftentimes, these replicas serve a specific purpose, such as read replicas, which are distributed across the world for faster reads for users. However, once you introduce these replicas, it makes the distributed systems much more complex, since the server that’s being written to has to figure out how to ensure that the read replicas are up to date. I remember strategies such as write-through and write-back but I’m sure we’ll cover it in this video.

Ok now let’s watch the video.

Definition

Replication, as I said before, is when the same data is on multiple nodes in a distributed system. This is not only necessary for speed improvements, but also for when one of the replicas goes down. This can happen for various reasons such as a software update, network partition, etc.

Of course, when the data doesn’t change. replication is very easy. You just spin up database servers, load them with data, and your customers will hit those replicas and always get data that is accurate with the rest of the system. The real world, however, oftentimes requires more. Websites like YouTube are constantly seeing new data come in and require updates to the replicas.

I mentioned RAID before, but that doesn’t apply here since RAID is used on a single computer with a single controller across multiple disks. We’re trying to tackle the problem of how we achieve replication across multiple computers, aka a distributed system.

State updates

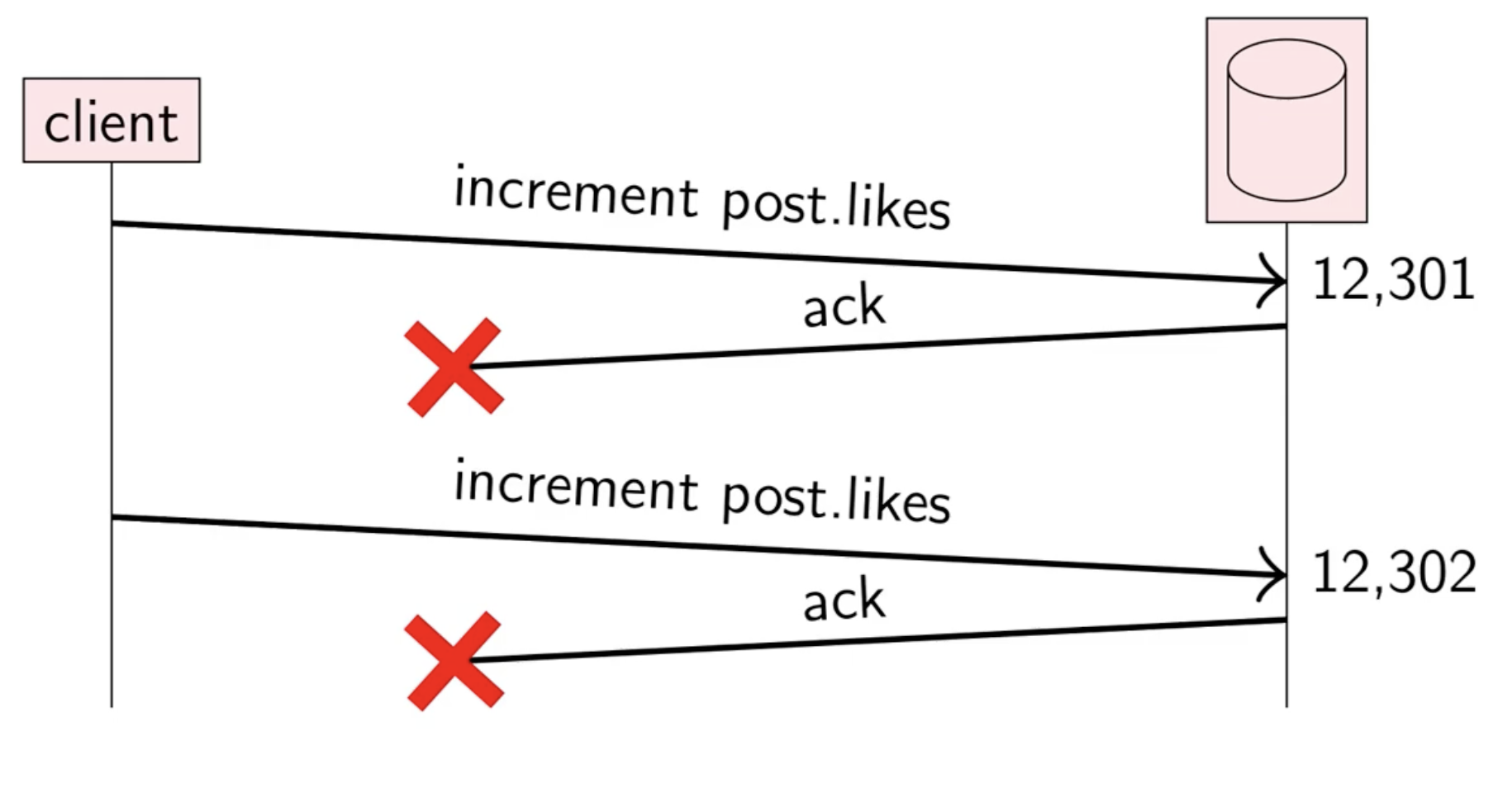

Let’s take an example of a user like a comment on YouTube. One way to do it is the request sent to the server is “increment post.likes”. So when the like button is pressed, the server updates the like amount in the database and then sends an acknowledgement back to the client so the client knows that the like has gone through. If the client doesn’t receive the acknowledgement, it knows to retry the request since there might’ve been a network issue.

But then you might run into a situation like this:

Here, the server receives the increment command but the acknowledgement was lost in transmission. From the client’s perspective, no ack has been received so it retries the request, possibly causing multiple likes from the same user.

Idempotency

To fix this issue, we can use an idempotent function, meaning a function where applying it multiple times has the same result as applying it once.

f(x) === f(f(x))An example of this operation is adding an element to a set. Since a set is unique, you can add the element 5 as many times as you want and it will have the same impact as adding it once. Increment a counter, however, is not idempotent.

So to solve the problem above, we can store the likes as a set and the request from the client would be adding their user ID to the set. If it receives no ack, it can retry safely.

Retry semantics choices

This leads to a choice of retries which depends on your use case

At-most-once

With At-most-once, you only send the request once. Here, it doesn’t matter if your function is idempotent since you will not be retrying it. If it succeeds, great, if it fails, oh well. An example of where this is useful is in logging systems. Oftentimes there isn’t a benefit of retrying a log (if it’s not critical) since it will just slow down the system.

At-least-once

With At-least-once, you keep retrying until the event is acknowledged. An example of this is the initial like update example, where a request can be duplicated.

Exactly-once

This is the same as At-least-once but we introduce an idempotent function since we are sending the same request many times.

Limitations with idempotency

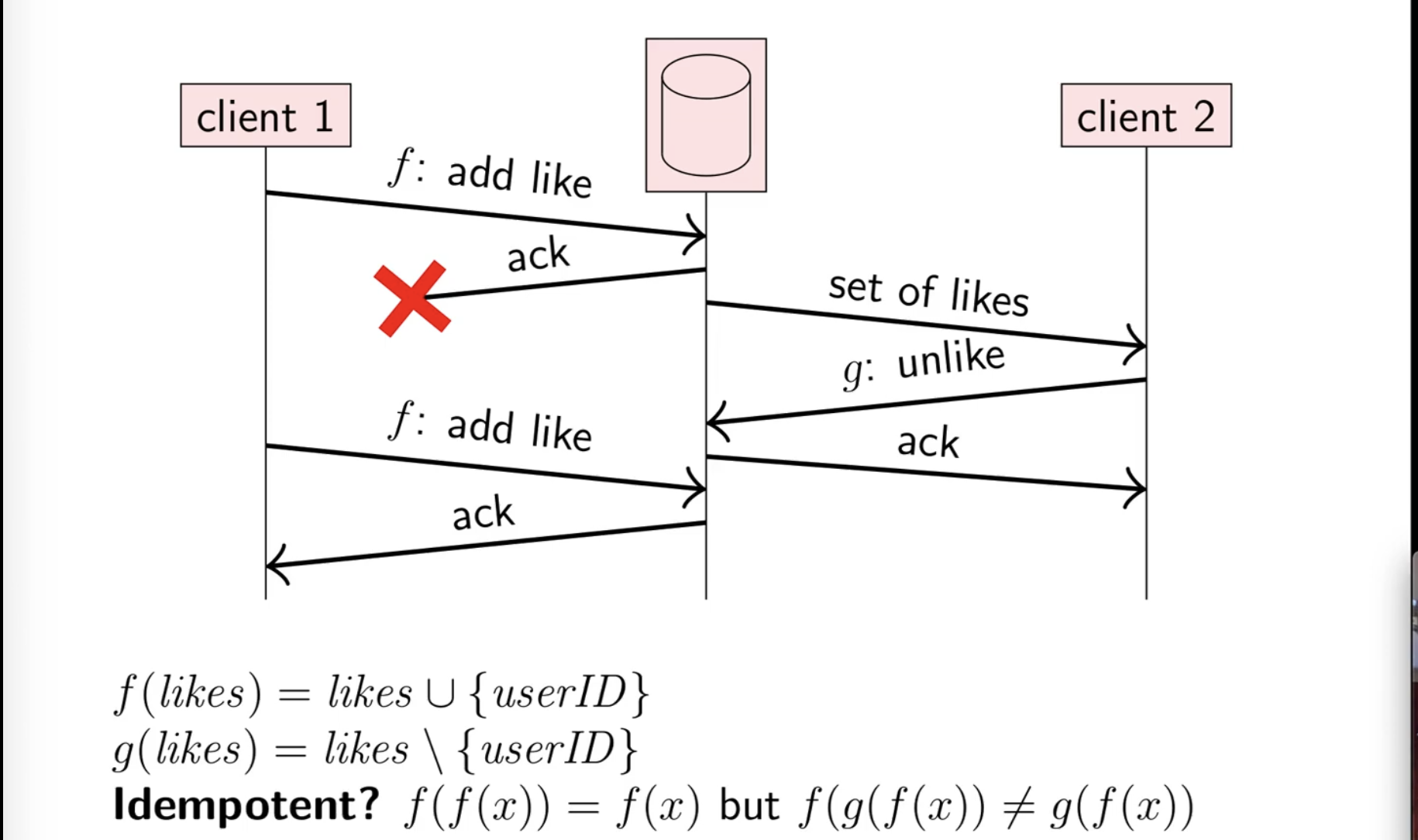

However idempotency is not a silver bullet since we can end up in a situation like this:

Assume two clients are logged into the same account with the same user ID.

Client 1 will send a like request which goes through (we’ll say it updates to a set of size 100) but the ack gets lost in transmission. No worries, we can retry it with no harm, right? Well if client 2 reads from the liked set and removes a like, the like count will go to 99, and then it’ll be added again when Client 1 retries. This is a bit inconsistent since Client 2 initially thinks UserID has liked the post, but Client 1 does not.

Another problem

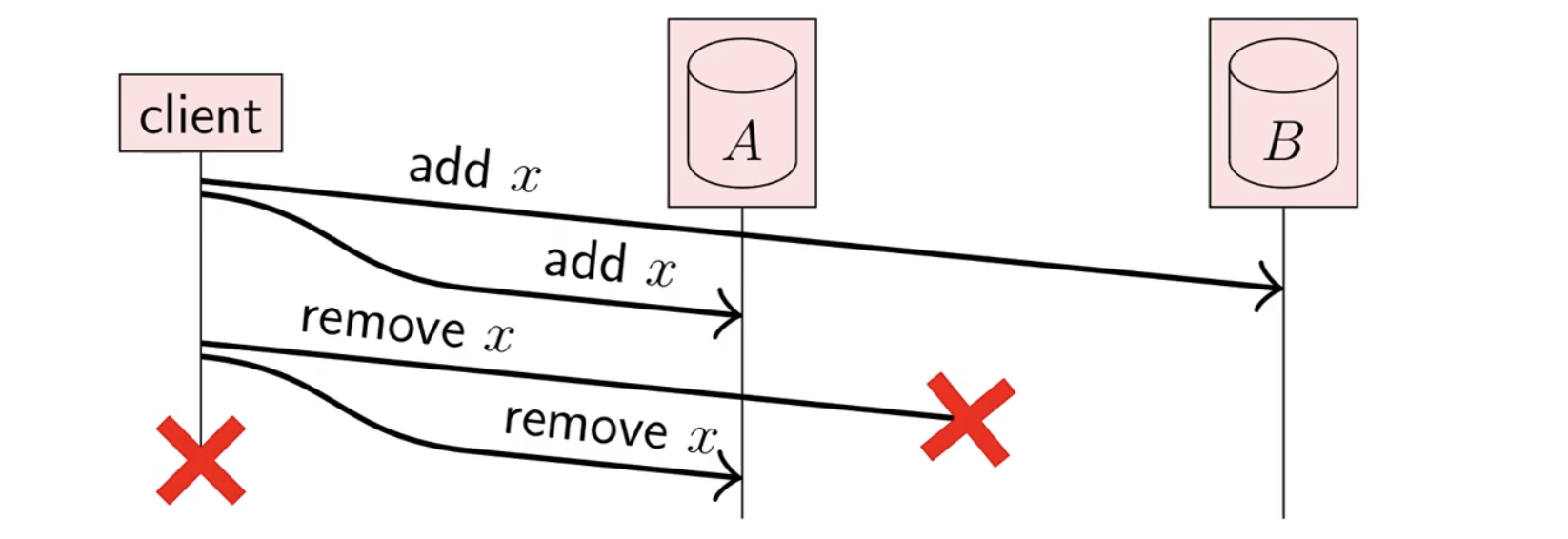

Let’s look at another example that illustrates a problem before we try to solve it.

Here, the user has added x to a set in replica A and replica B (which were both successful) and then attempted to remove x. Keep in mind this operation is not complicated from the client’s POV, it simply looks like this:

const x = 3;

await set.add(x);

await set.remove(x)However, if the set is in a distributed system, it replicates the set to multiple replicas (A and B in this case).

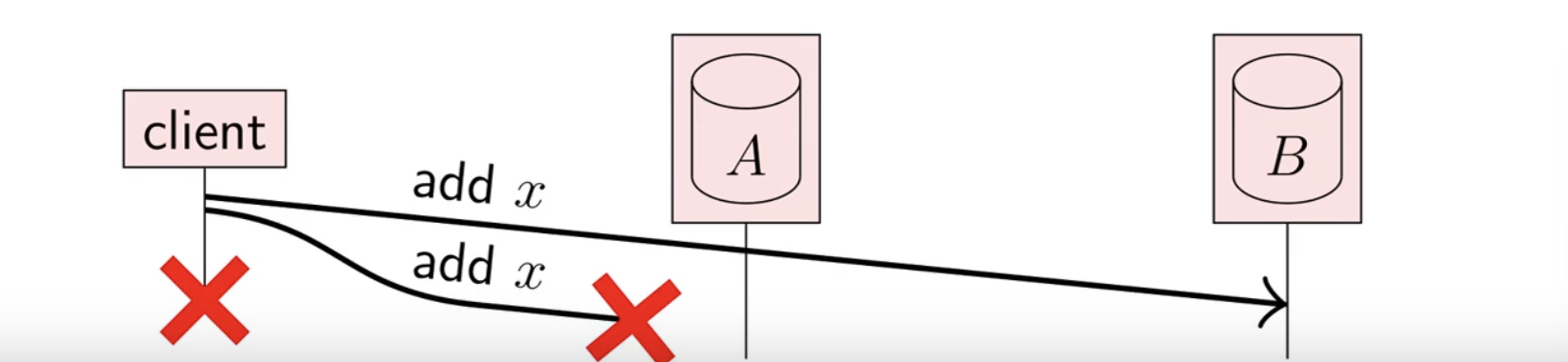

With this example, we’re left in a state where x is not in A but x is in B. Notice how this end state is identical to this one:

Here, x is not in A but x is in B, so the state is identical. However, the intention from the user is not the same. In example 1, the user’s code looks like this:

const x = 3;

await set.add(x);Here, they did not want to remove the element from the set. So how we differentiate the two?

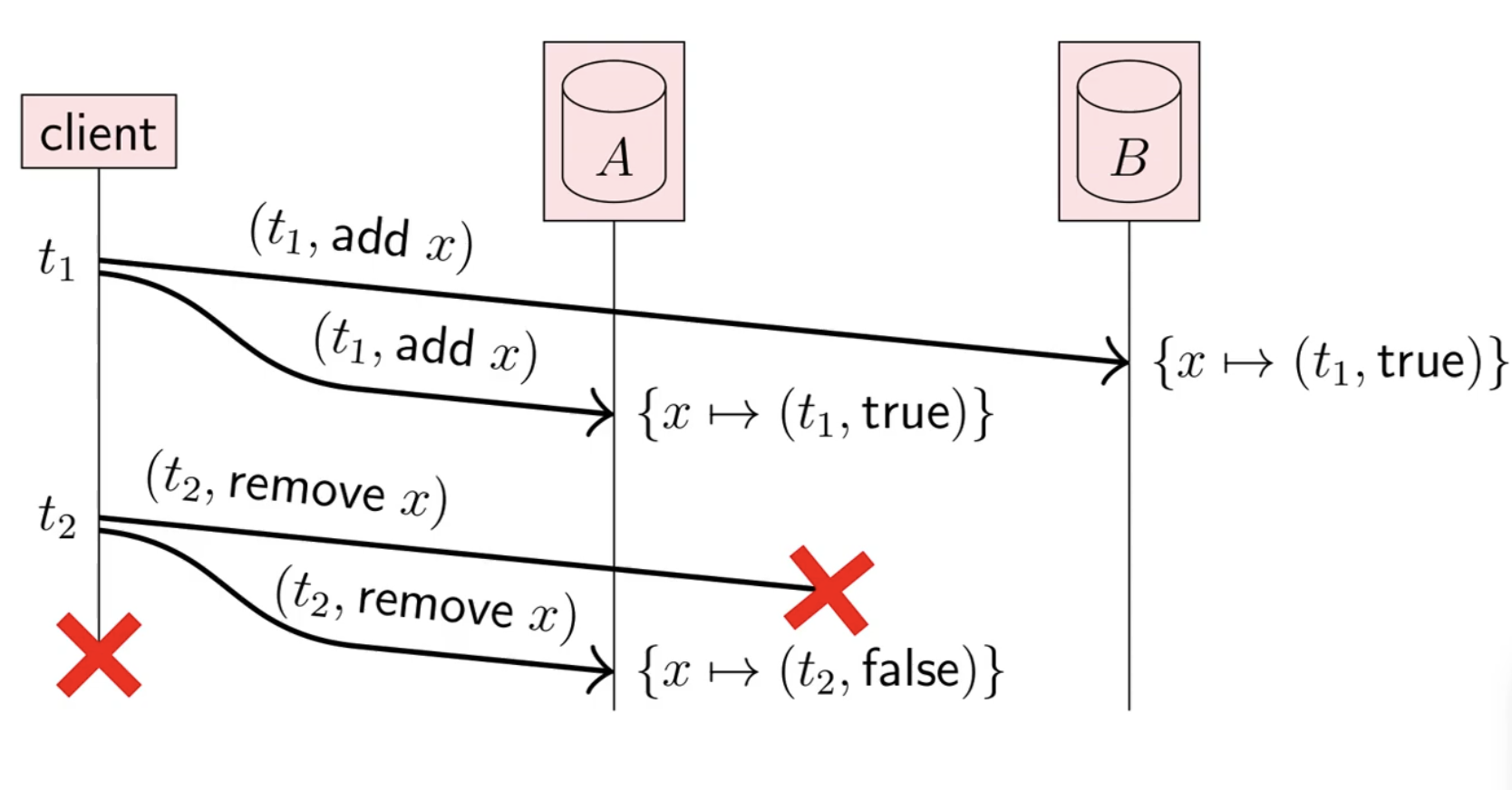

Timestamps and tombstones

The way to differentiate these two replicas is to attach a logical timestamp (see my earlier posts on logical time) and not “soft delete” the elements. So if the client wants to add an element to the set, the replicas will see something like (t1, true) signifying the (timestamp, isPresent). When the client deletes the element, the replicas see (t2, false).

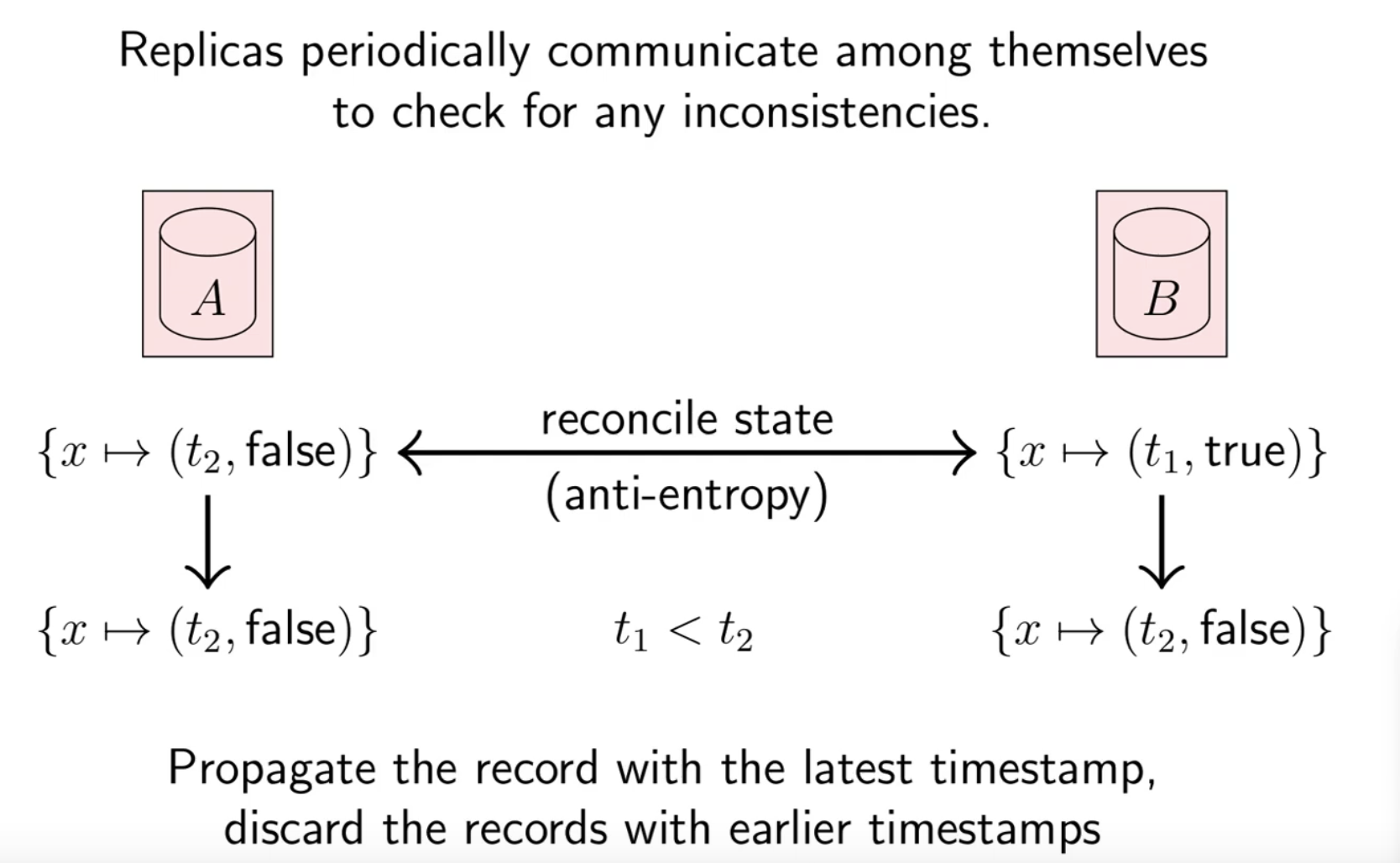

The idea of this “soft delete” is also called a tombstone, since we are keeping the removed data around to do the differentiation. Eventually these tombstones can be garbage collected. Now that there is a clear distinction between the replicas, we can run a reconciliation algorithm by comparing timestamps and keeping the state where the timestamp is latest.

Notice how A doesn’t change since it has the latest timestamp, but B updates to the state of A since it has an earlier timestamp, signifying it is out of date.

Concurrent writes

If we have two clients that send requests concurrently, there are two common approaches:

- Last writer wins, where we use Lamport clocks in order to use the total ordering. But here, there may be data loss since we just keep the value with the higher timestamp.

- Multi-value register, where we use vector clocks and only overwrite values if their vector clocks signify that t2 is strictly greater than t1. Otherwise, we keep both values and have the application resolve the conflict.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBUCF1WGI_I&t=12s (DDIA Lecture series)