Coffee Codex - The Log

Introduction

I’m at Nana’s Green Tea in Bellevue, WA and today I’m learning about the fundamentals of the log in distributed systems from this blog post from LinkedIn.

I’m trying matcha for the first time in this series.

I’m interested in this because I covered how the backend of Convex works in a previous post and they heavily utilize a transaction log in order to maintain serializability. I’m curious how typical a solution like theirs is.

What is a Log

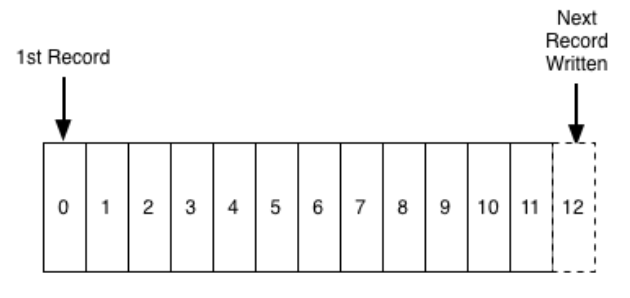

A log at its core is a very simple data structure, it’s append-only and totally-ordered. It looks like this:

There are some problems with just storing data in an append-only log as I’m sure we’ll cover. Some that immediately come to mind are that (1) reading records will be slow (Convex fixes this with indexes), (2) Durability of the log. Obviously implementing a “log” in a programming language can just be an array or linked list where you only allow .push operations, but that lives in memory so I’m curious to see how to make a log durable.

Once we have a log, it can be used as an authoritative source of information. We often see this in techniques like write-ahead-logging to help crash recovery.

Applications in distributed systems

Timing is notoriously hard in distributed systems, I have several blog posts covering the problems with physical clocks and usage of atomic clocks. The great thing about a log is that the timestamp of a log entry is just the index which acts as a logical timestamp.

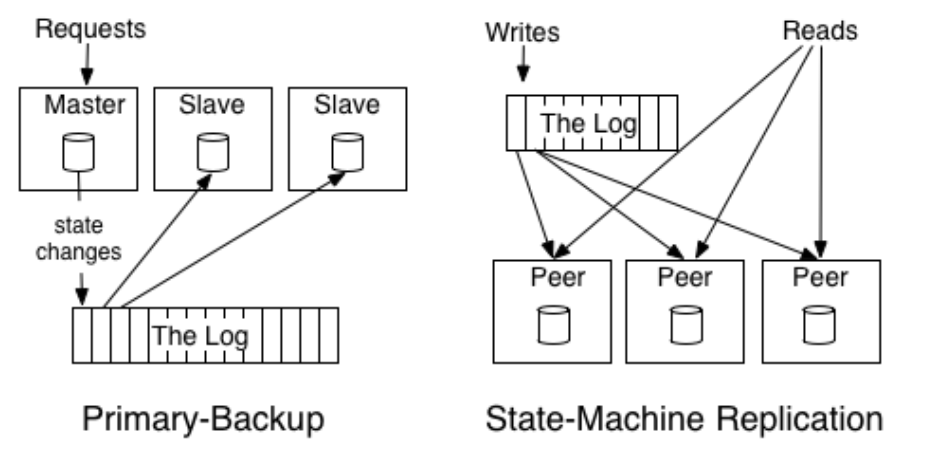

There’s a distinction between a state-machine (active-active) and primary-backup (active-passive) model for logging. Let’s say we have an arithmetic program and each node has a starting state of the number 0. Then, the system gets a request to “Add 5”. What do we add to the log?

| Option | What’s logged | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Log the request | “Add 5” | Just store the command (the intent). Each replica executes it. |

| Log the state change | “New value = 5” | Store the resulting state. Replicas don’t re-run the logic, just apply the result. |

With the active-active model, we opt for the first approach where we store the intent. With the active-passive model, the leader stores the resulting value.

Even though people talk about the log like it’s a single thing, there isn’t one big central log sitting somewhere. Each node keeps its own local copy on disk, and consensus protocols such as Raft or Paxos make sure those copies all contain the same entries in the same order. From the system’s perspective, it behaves like one shared global log. Every node replays that log to stay in sync, even if one falls behind or crashes.

In the active–active model, multiple nodes can handle requests directly. Since they can all propose new entries, they have to coordinate through consensus to agree on the next command and its position in the log.

In the active–passive model, things are simpler because only the leader handles requests and writes to the log. The other nodes just replicate whatever the leader writes. Consensus still matters here, but mainly for leader election and ensuring everyone agrees on who is in charge.

Both approaches rely on consensus, just in different ways. Active–active uses it to agree on what goes into the log, while active–passive uses it to agree on who gets to write to it. Either way, consensus keeps all the nodes aligned and moving together.

Next time we’ll continue this with some more applications of using a distributed log!