Coffee Codex - Reverse engineering twitch.tv

Introduction

I’m at Woods Cafe in Bellevue, WA and I’m learning about streaming technology by reverse engineering Twitch. I can’t know how the backend of Twitch works, so I’m going to focus on the Client requests/responses to understand how a streaming platform works.

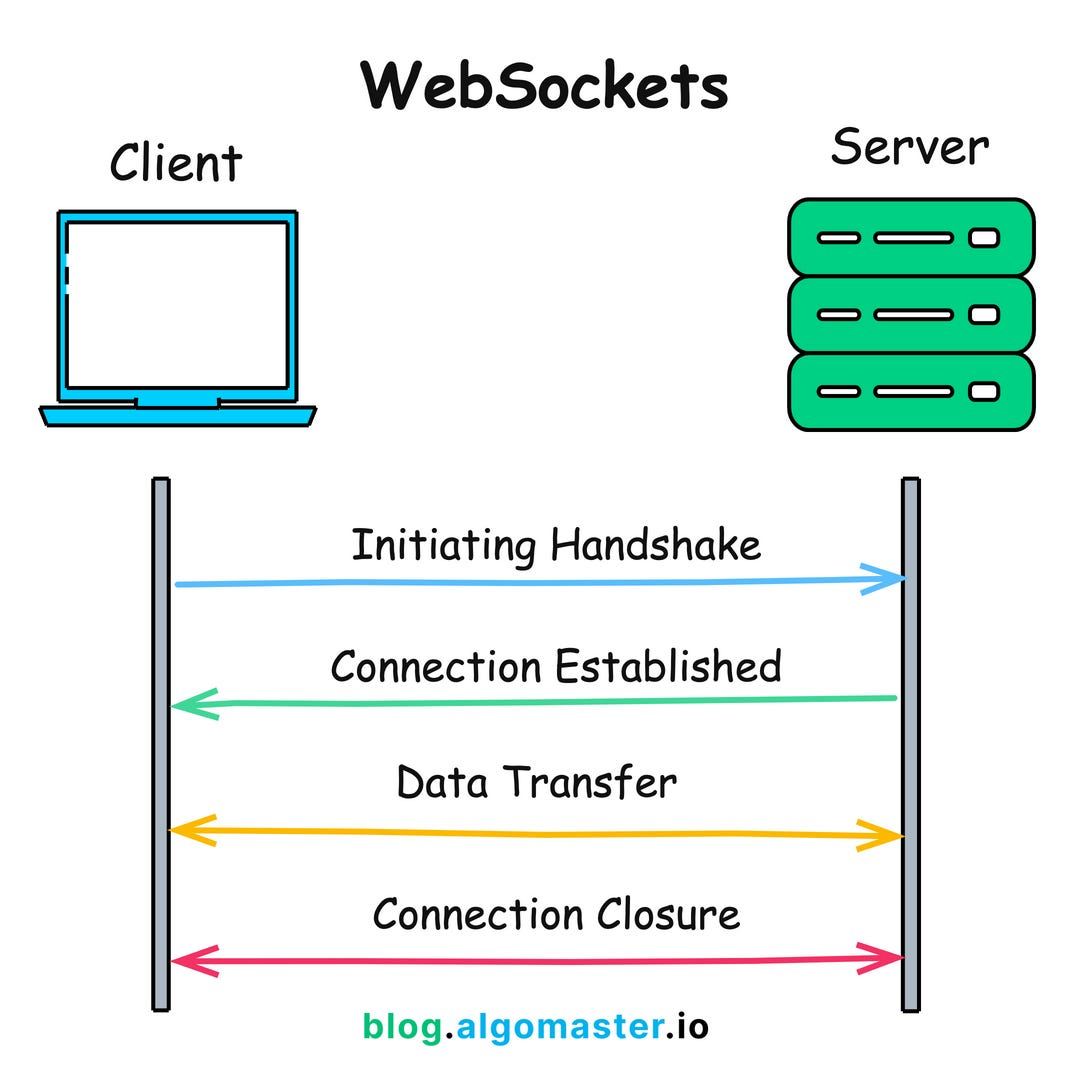

Websocket connections

The first thing I looked for was websocket connections. Intuitively it makes sense for twitch to operate a lot of their requests through websockets, so let’s take a look.

For those unfamiliar, a websocket connection starts as an HTTP request but then upgrades to provide persistent, bidirectional communication between a client and a server. Think of a chat app - with HTTP’s request-response model, clients would need to constantly poll the server asking “any new messages?” which is inefficient and creates delays. WebSockets allow the server to immediately push new messages to all connected clients.

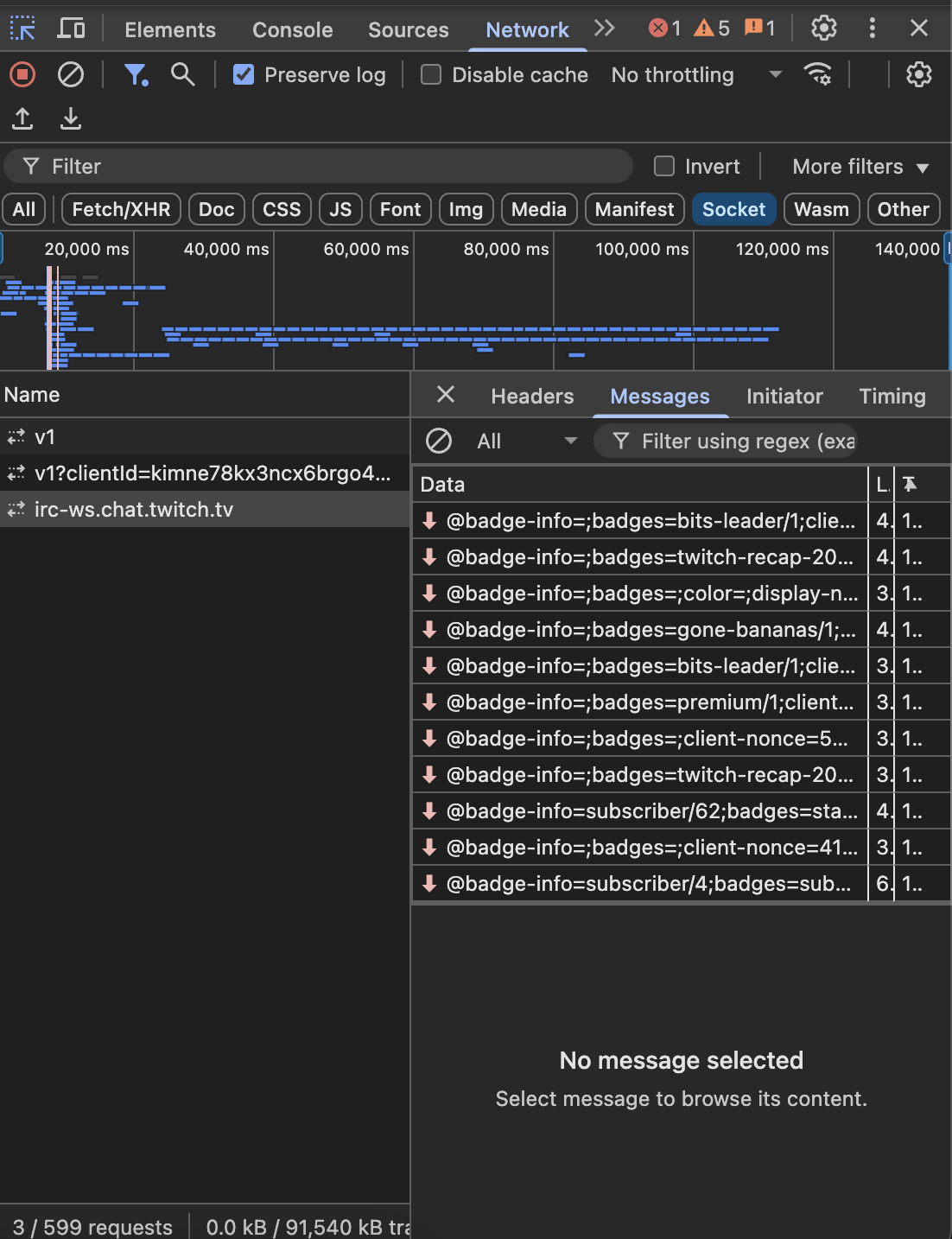

As I open a twitch stream (in this case https://www.twitch.tv/melkey), I see three websocket connections open:

1. GET wss://pubsub-edge.twitch.tv/v1

2. GET wss://hermes.twitch.tv/v1?clientId=<CLIENT_ID>

3. GET wss://irc-ws.chat.twitch.tv/I won’t share a har file at the risk of sharing any secret information but this is a high level overview.

pubsub-edge

This connection seems to include a heartbeat of the format

Client: {"type":"PING"}

Server: { "type": "PONG" } which get sent every 4 minutes.

After the initial handshake, I see several LISTEN requests being sent automatically. Here are some examples:

{"data":{"auth_token":"[REDACTED]","topics":["pv-watch-party-events.[CHANNEL_ID]"]},"nonce":"[NONCE]","type":"LISTEN"}

{"data":{"auth_token":"[REDACTED]","topics":["user-extensionpurchase-events.[USER_ID]"]},"nonce":"[NONCE]","type":"LISTEN"}

{"data":{"auth_token":"[REDACTED]","topics":["bits-ext-v1-transaction.[CHANNEL_ID]-[EXTENSION_ID]"]},"nonce":"[NONCE]","type":"LISTEN"}

{"data":{"topics":["extension-control.[CHANNEL_ID]"]},"nonce":"[NONCE]","type":"LISTEN"}

{"data":{"topics":["broadcast-settings-update.[CHANNEL_ID]"]},"nonce":"[NONCE]","type":"LISTEN"}

{"data":{"auth_token":"[REDACTED]","topics":["channel-drop-events.[CHANNEL_ID]"]},"nonce":"[NONCE]","type":"LISTEN"}Each gets a response like:

{"type":"RESPONSE","error":"","nonce":"[NONCE]"}What’s interesting is that I didn’t manually subscribe to anything - the Twitch client automatically subscribes to relevant events when you open a stream. These subscriptions cover various real-time events like watch parties, extension purchases, bits transactions, extension controls, broadcast settings updates, and channel drops.

So when 1000 people watch the same stream, each gets their own set of these subscription messages with their own auth_token and relevant user/channel IDs. This allows for real-time notifications without the overhead of polling.

hermes

The second connection is to something called Hermes - probably an internal codename Twitch uses. The request looks like:

GET wss://hermes.twitch.tv/v1?clientId=<CLIENT_ID>The clientId in the query string makes me think this is part of a newer PubSub system, maybe built for better scalability.

When it connects, Hermes sends back a welcome message:

{

"welcome": {

"keepaliveSec": 15,

"recoveryUrl": "..."

}

}The keepaliveSec tells the client to expect pings every 15 seconds, and the recoveryUrl is probably for reconnecting if the connection drops.

What’s interesting is that Hermes is completely separate from pubsub-edge, even though they both handle real-time events. While pubsub-edge deals with extensions and channel stuff, Hermes seems like a newer, more streamlined PubSub system.

It looks like Hermes handles core client features that need real-time updates (video state, stream info, drops), here are some examples:

{"type":"subscribe","id":"[SUB_ID]","subscribe":{"id":"[SUB_ID]","type":"pubsub","pubsub":{"topic":"hype-train-events-v1.rewards.[USER_ID]"}},"timestamp":"[TIMESTAMP]"}

{"type":"subscribe","id":"[SUB_ID]","subscribe":{"id":"[SUB_ID]","type":"pubsub","pubsub":{"topic":"user-drop-events.[USER_ID]"}},"timestamp":"[TIMESTAMP]"}

{"type":"subscribe","id":"[SUB_ID]","subscribe":{"id":"[SUB_ID]","type":"pubsub","pubsub":{"topic":"chatrooms-user-v1.[USER_ID]"}},"timestamp":"[TIMESTAMP]"}

{"type":"subscribe","id":"[SUB_ID]","subscribe":{"id":"[SUB_ID]","type":"pubsub","pubsub":{"topic":"user-subscribe-events-v1.[USER_ID]"}},"timestamp":"[TIMESTAMP]"}irc-ws.chat.twitch.tv

This connection controls the Twitch chat system, and it’s actually built on top of IRC (Internet Relay Chat) — a messaging protocol that dates back to the late 1980s. While IRC is old, it’s still incredibly efficient for real-time text communication, and Twitch has customized it to support modern features.

When the Twitch client connects, it sends a series of IRC commands to authenticate and identify the user

CAP REQ :twitch.tv/tags twitch.tv/commands

PASS oauth:<token>

NICK <username>

USER <username> 8 * :<username>After authentication, the client joins a channel with:

JOIN #<StreamerName>From that point on, it receives all the chat messages, user actions (like joins, leaves), and moderation events (bans, timeouts, etc.) for that channel — in real-time.

Each message can carry metadata like user badges, colors, emotes, and display names. For example:

@badge-info=subscriber/6;badges=subscriber/6;color=#1E90FF;display-name=Viewer123 :viewer123!viewer123@viewer123.tmi.twitch.tv PRIVMSG #streamername :this stream is awesome!This message might look like a mess of symbols at first glance, but once you break it down, it’s surprisingly structured. Twitch is using old-school IRC under the hood, just layered with modern metadata.

@badge-info=subscriber/6;

badges=subscriber/6;

color=#1E90FF;

display-name=Viewer123 :viewer123!viewer123@viewer123.tmi.twitch.tv

PRIVMSG #melkey :this stream is awesome!The @ section is full of key-value pairs — metadata that Twitch attaches to the message. Stuff like how long someone’s been subscribed (subscriber/6 = 6 months), what their name color is, and how their display name should appear.

The middle part (viewer123!viewer123@…) is classic IRC-style user identification.

PRIVMSG #melkey just means “send this message to the channel #melkey”, which looks to be for public methods as well despite its name.

And the actual chat message is “this stream is awesome!”.

Streaming Connection

The WS connections are great, but they don’t handle the actual streaming of data, so let’s look into the fetch requests.

Every second there’s a swarm of requests related to HTTP Live Streaming (HLS) which is a live streaming protocol created by Apple.

GET https://use15.playlist.ttvnw.net/v1/playlist/<long_token>.m3u8This is Twitch asking for a master playlist file using the HLS protocol. The .m3u8 file extension is the giveaway — it’s part of how HLS organizes video streaming. What’s cool is that the URL includes a massive token, likely encoding session info, user permissions, stream context, and maybe even playback settings. It’s clearly meant to be secure and specific to each viewer.

The domain ttvnw.net is Twitch’s CDN domain, and use15 probably refers to a regional edge (U.S. East 15 or similar). This tells me Twitch is using a geographically distributed playlist system — so when you watch a stream, your client fetches video instructions from the nearest edge server to reduce latency and improve reliability.

The playlist request itself is just a regular HTTP GET, which makes it CDN- and browser-friendly. Once the client has this playlist, it knows how to grab the actual video segments — but I’ll get into that part next.

Response

The .m3u8 file Twitch requests is a playlist, not a video file itself. It’s a structured list of what video chunks to download and in what order. It’s part of the HLS format, which breaks streams into small segments (usually a few seconds each) that the client downloads one by one.

The response is structured like this:

Header/version

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-VERSION:3Playback control indicating that each transport stream (.ts) segment is <= 6 seconds

#EXT-X-TARGETDURATION:6

#EXT-X-MEDIA-SEQUENCE:1454

#EXT-X-TWITCH-LIVE-SEQUENCE:1454The next part includes timing metadata from Twitch:

#EXT-X-TWITCH-ELAPSED-SECS:2908.000

#EXT-X-TWITCH-TOTAL-SECS:2940.000This tells the client how long the stream has been running in total and how much the viewer has seen (or buffered). It helps Twitch synchronize live indicators and playback timing across devices.

Following that are #EXT-X-DATERANGE tags. These are Twitch-specific markers that embed metadata about the session, stream source, ad triggers, or other internal events. Example:

#EXT-X-DATERANGE:ID="playlist-session-1752347250" ...They don’t affect playback directly but help Twitch annotate the stream (possibly for analytics, tracking events like ad breaks, or stream switches).

Then come the actual video segments which are what your video player downloads and plays:

#EXT-X-PROGRAM-DATE-TIME:2025-07-12T19:08:20.925Z

#EXTINF:2.000,

https://video-edge-url.segment1.tsAt the end of the playlist, Twitch includes a prefetch hint for the next section:

#EXT-X-TWITCH-PREFETCH:https://video-edge-url.prefetch-segment.tsTwitch doesn’t use HTTP/3 from what I can tell so they are using TCP to retrieve the stream data for viewers to watch, but it’s certainly possible they use UDP for the streamer -> twitch connection.

And that’s what I could figure out related to twitch streaming from a chatter’s POV. It would be great if twitch releases more technical deep dives on how they optimize streamin in their backend!

References

- twitch.tv and browser tools