Coffee Codex - Fluid Compute

Introduction

I’m at home for the first time in this series!

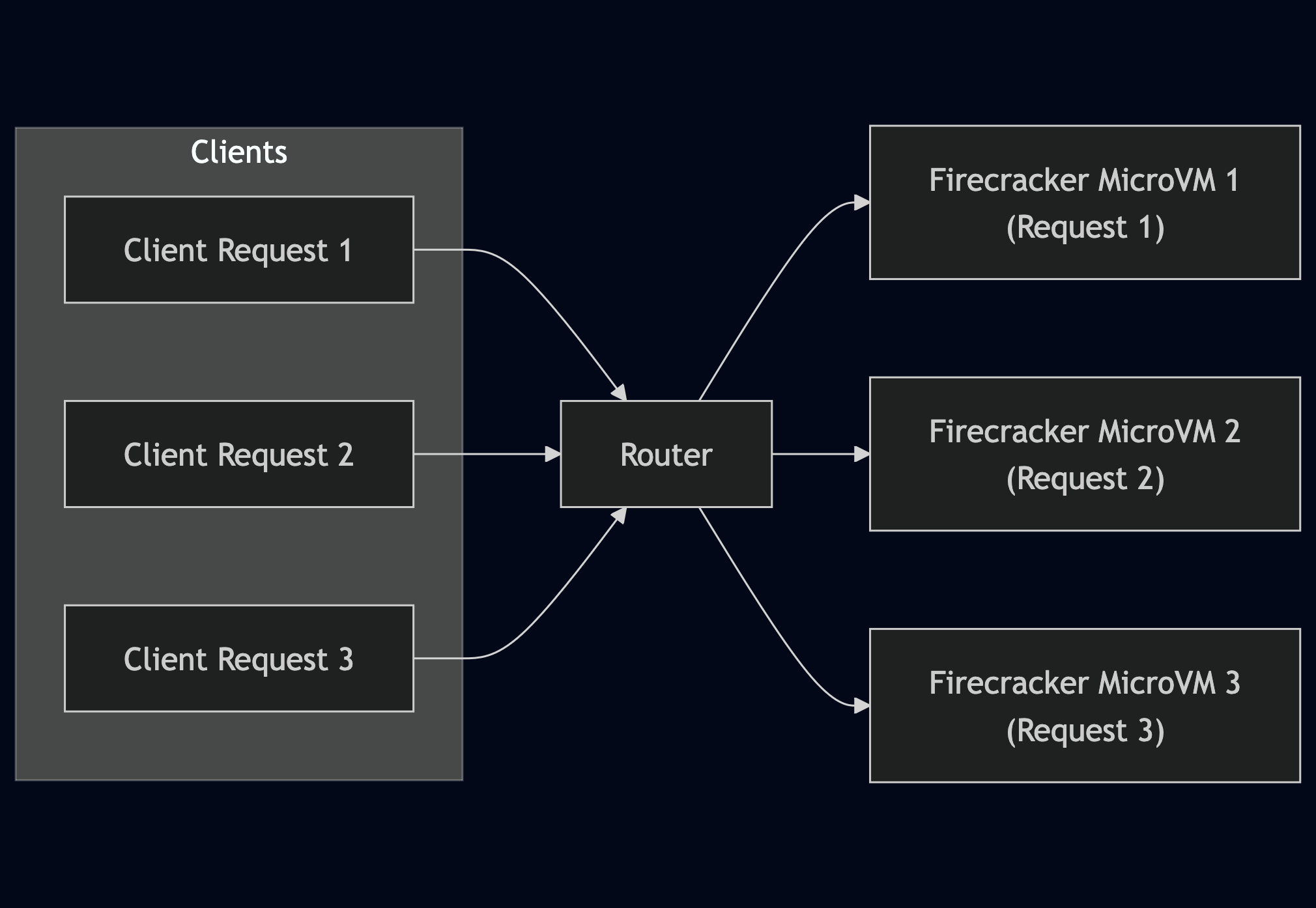

In the last post, I started learning about Dropbox’s Magic Pocket technology. I’ll continue exploring it next time, but I saw an interesting challenge by @rauchg to figure out how Vercel’s Fluid Compute works. I’ve looked into how Hive works before and I’ve found it’s pretty similar to the Lambda architecture (slots in servers with a Firecracker microVM running on the host’s KVM capabilities) from previous posts:

So let’s learn about Fluid Compute!

What is Fluid?

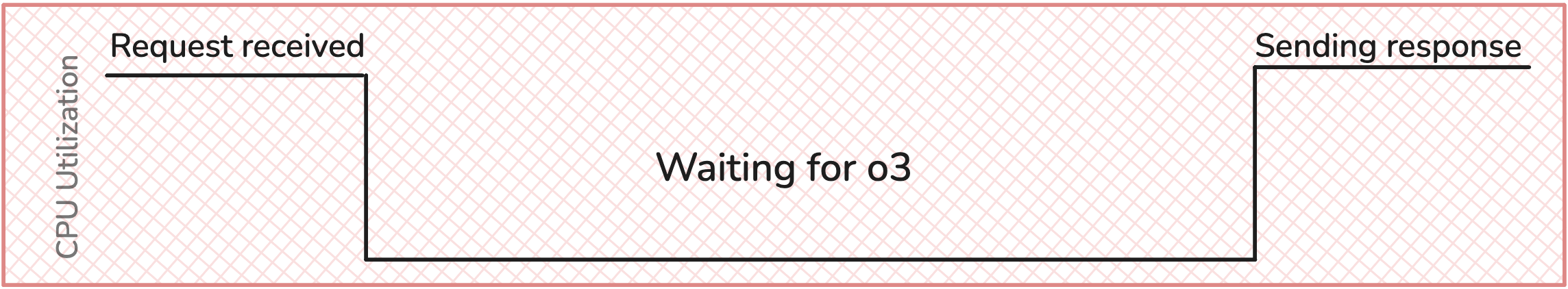

Imagine you have a chat app that gives you access to GPT-o3 Deep Research, which can often take over 5 minutes to give you a response. In a typical serverless infrastructure (like Lambda), this one request will get a slot in a bare-metal EC2 instance which runs a Firecracker microVM. The request will have complete ownership over the microVM until the execution completes.

But as we said before, o3 can be doing I/O for a long time, so the CPU is effectively idle during this time.

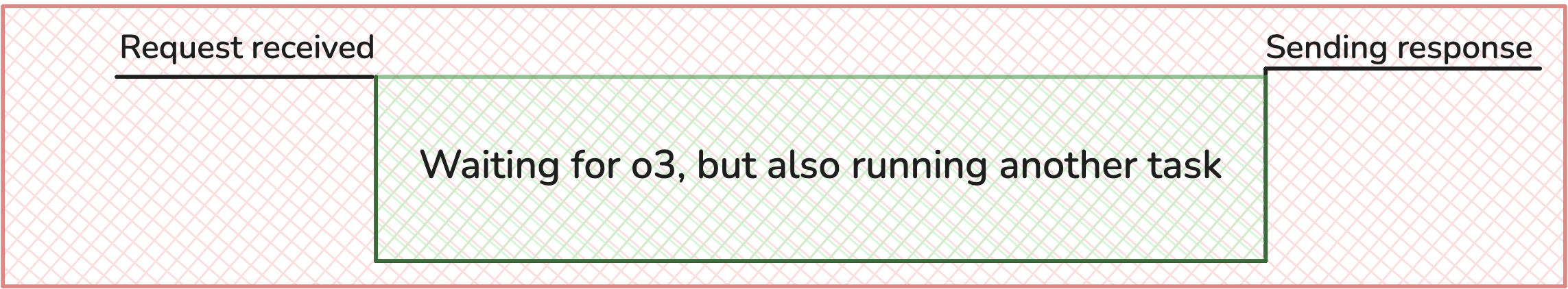

During this time, it would be nice if another request can take advantage of the idle CPU and run another request concurrently.

That’s what Fluid compute allows you to do.

Concurrency

The classic example of concurrency is a waiter at a restaurant. It wouldn’t be very efficient if a waiter only served one customer until they leave. Instead, the waiter is also taking orders while the chefs are cooking so they can maximize the amount of customers served. In Javascript terms, when a piece of code awaits, we can execute another request.

It’s important to know that this isn’t a new concept in operating systems, but it is slightly different. Concurrency has existed for a long time but typically by time slicing the CPU. This is because the OS can pre-empt tasks that might be taking too long by interrupting them and starting a new task to make space for quicker, higher priority tasks. With Fluid, it doesn’t seem like Vercel pre-empts tasks, but instead relies on language specific asynchronous behavior to decide when another task can be started (please correct me if I’m wrong).

This means that the function router has to be smart. If we take a random approach to assigning VMs, then we might end up with a situation where Task A has a 5 second I/O operation where Task B has a 30 second CPU-bound operation. If Task B gets scheduled during Task A’s I/O, then we will see higher latency for Task A. Luckily, this is a scheduling problem, and there are decades of research on scheduling that can help us out. However there are new conditions to consider, such as using our knowledge of AI models to our advantage.

Routing

Let’s say we know that we have 1 Deep Research request and 3 GPT-4o requests in our queue. The routing layer should be smart enough to know that the 4o requests can be sent during the heavy I/O from Deep Research. There are, of course, other metrics to think about when distributing tasks such as availability, load, proximity, etc.

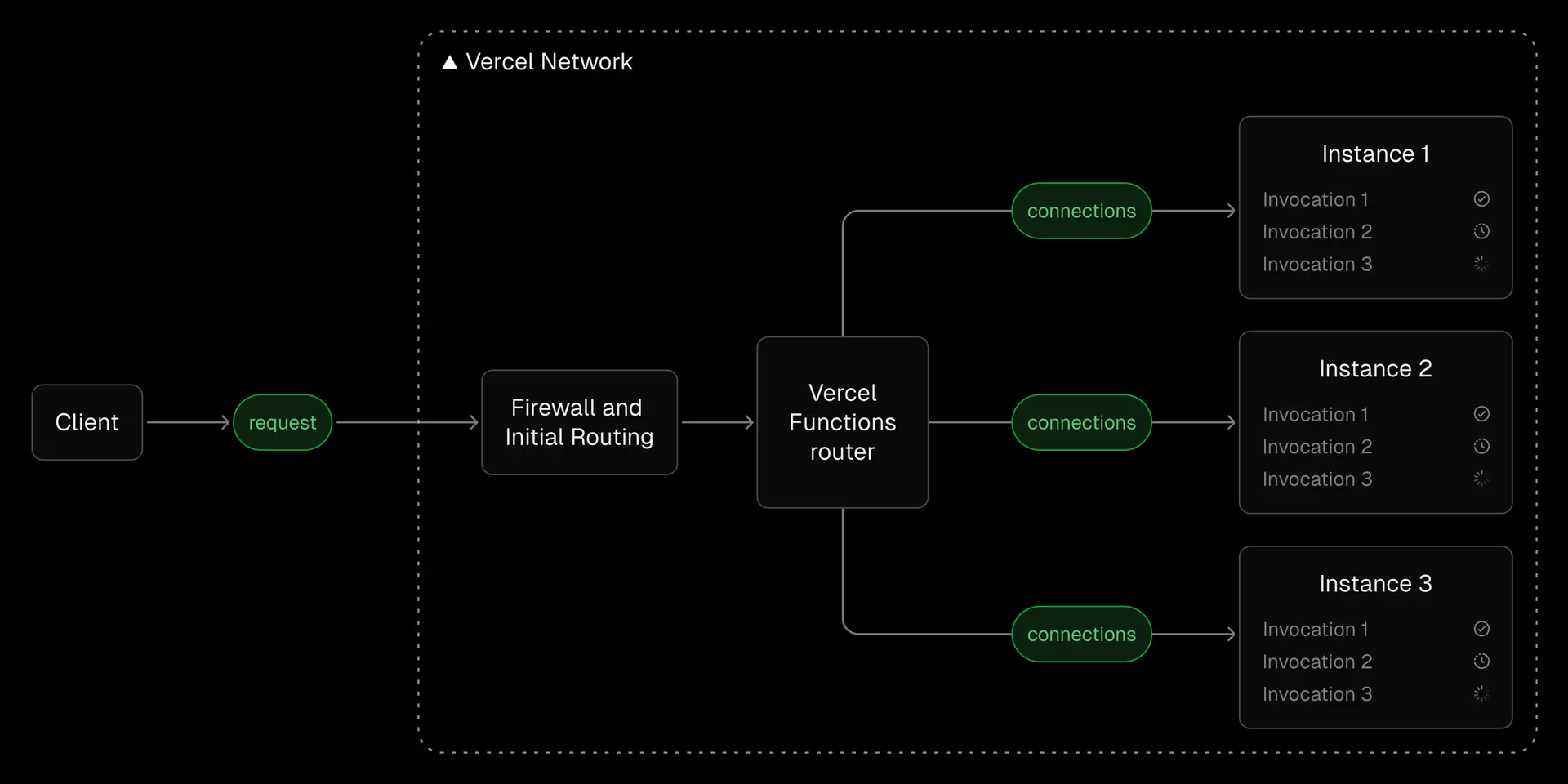

When a Vercel function is invoked, the request hits a Vercel Point of Presence (PoP), gets inspected through the Vercel firewall, checks the cache, then moves to the router. From the router, the Vercel function route communicates with function instances using persistent TCP tunnels. I could make a diagram for this but Vercel has a really good one already.

The communication to and from the router is bidirectional, allowing responses to be streamed back to the client.

Function instances

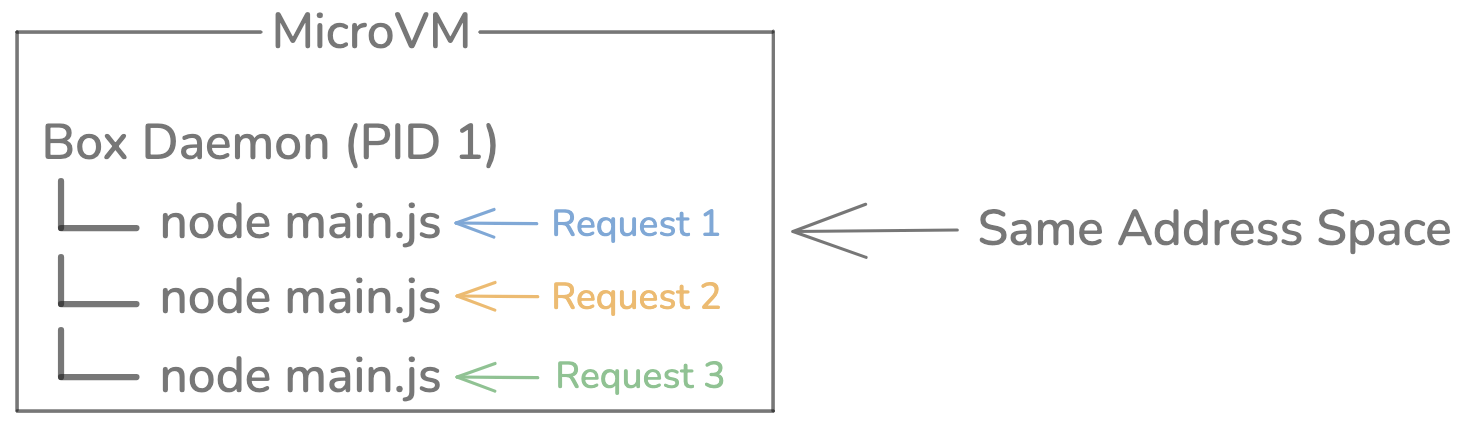

Ok, now lets get to the actual microVMs. The typical approach that Lambda takes is 1 request takes control of 1 microVM which gives us great isolation. Now, Vercel has intra-function concurrency, allowing multiple requests to operate on the same microVM.

The microVM is presumably run with Firecracker and communicates with a bare metal EC2 instance via a hypervisor (KVM). Just like Lambda, the bare metal instance is likely split into many slots (called “cells” in Hive).

The Box Daemon (written in Rust btw) is a supervisor responsible for launching the function inside the MicroVM, enforcing resource limits, and monitoring execution. It sets up sandboxing measures such as seccomp (system call filters) and Linux namespaces within the VM. The Rust supervisor therefore primarily acts as a gatekeeper: it boots the language runtime (Node or Python), passes in events (HTTP requests), and ensures the function cannot exceed its allocated CPU time or memory. If the function process crashes or behaves unexpectedly, the supervisor can tear down and restart the MicroVM, preserving the isolation guarantees.

Security / Threat Model

The traditional way Lambda does isolation (1:1 mapping between request and microVM) has a good isolation boundary. Even in the case of a user breaking out of userspace into kernel space, they are still isolated within the microVM.

The threat model becomes a bit more clear when we consider operating systems principles. There is a risk of context switching between two processes, in that there is the possibility of shared memory being accessed. Modern operating systems achieve isolation primarily with process boundaries: every process owns a private address-space managed by the MMU, and the kernel flips page-tables on a context-switch. When Lambda maps one request → one microVM, the isolation boundary is even stronger than a normal process switch:

| Boundary | Who performs the switch? | What is protected? | Cost per switch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thread ⇒ Thread | Kernel scheduler | Threads share one address-space – only registers/stack differ | Cheap (no TLB shoot-down) |

| Process ⇒ Process | Kernel + MMU | Private user-space memory; kernel memory is shared | Moderate (TLB flush, page-table reload) |

| MicroVM ⇒ MicroVM | Hypervisor (KVM/Firecracker VMM) | Full kernel + user isolation; distinct virtual devices | Expensive (VM-exit/entry, device emulation) |

With Fluid Compute the outside boundary stays at the VM level (row 3), but inside the VM Vercel now runs many invocations concurrently in a single Node/Python process. That changes the inner isolation boundary to look more like row 1:

Because of this multi-tenant paradigm, there are more attack vectors to consider. Note that I’m calling the system “multi-tenant” since one instance serves many requests but I assume each function is tied to one customer.

We have to consider noisy neighbors with intra-function concurrency because it’s now possible for one request to hog the entire microVM, assuming there’s no pre-emption. Vercel does have limits in place for execution time of these functions and monitors communicating back to the router to indicate that a specific instance should not accept more traffic.

In concurrent mode, global variables are now possible. It’s good to know that Google has been doing concurrent functions for a while, and according to them, “when concurrency is enabled, Cloud Run does not provide isolation between concurrent requests processed by the same instance. In such cases, you must ensure that your code is safe to execute concurrently” - Google. So the possibility of another request accessing or clobbering data in a shared memory space exists and is something that developers must be mindful of (ie by using AsyncLocalStorage). Otherwise, concurrency may be turned off :(

But what happens if something really goes wrong? Like what if one of the requests causes a segfault? If there are 3 requests on a single microVM, all 3 will experience a system failure. Presumably, the supervisor has knowledge of the system, collects metrics, and can intelligently restart and reallocate the microVMs. My assumption is the task that caused the segfault would now be isolated and have its concurrency set to 1 to prevent the same accident from happening again.

It’s also possible for malicious code to exist in memory. Say an attacker write shellcode to address 0xc0ffee. With a concurrent system, it’s certainly possible for another request to read and possibly execute that same data. While Vercel has a special /tmp directory for filesystem writes, injecting shellcode could be much more serious. ASLR is likely used to randomize the memory layout and snapshots would be generated on every deployment. The guest kernel should enforce “write-or-execute” (W⊕X). Pages mapping /tmp, heap allocations, or JIT data segments are non-executable. V8’s JIT flips page permissions only while emitting code, then locks them back to read-only and executable (RX). Attempting to jmp 0xc0ffee lands in a non-executable page and triggers another segfault—again caught by the supervisor.

What a bunch of fun problems to solve!

References

- https://vercel.com/blog/serverless-servers-node-js-with-in-function-concurrency

- https://vercel.com/blog/a-deep-dive-into-hive-vercels-builds-infrastructure

- https://vercel.com/docs/functions/fluid-compute

- https://www.reddit.com/r/nextjs/comments/1iibnj2/eli5_vercels_fluid_compute

- https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=43067938

- https://x.com/cramforce/status/1786454937834242374

- https://www.usenix.org/system/files/nsdi20-paper-agache.pdf

- ChatGPT for clarifications